Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs or pelvis.

Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and enlarged veins in the affected area, but some DVTs have no symptoms. The most life-threatening concern with DVT is the potential for a clot (or multiple clots) to detach, travel through the right side of the heart, and become stuck in arteries that supply blood to the lungs. This is called pulmonary embolism (PE). Both DVT and PE are considered as part of the same overall disease process, which is called venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE can occur as an isolated DVT or as PE with or without DVT. The most frequent long-term complication is post-thrombotic syndrome, which can cause pain, swelling, a sensation of heaviness, itching, and in severe cases, ulcers.

The mechanism of clot formation typically involves some combination of decreased blood flow rate, increased tendency to clot, and injury to the blood vessel wall. Risk factors include recent surgery, older age, active cancer, obesity, personal history and family history of VTE, trauma, injuries, lack of movement, hormonal birth control, pregnancy and the period following birth, and antiphospholipid syndrome. VTE has a strong genetic component, accounting for approximately 50 to 60% of the variability in VTE rates. Genetic factors include non-O blood type, deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S and the mutations of factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A. In total, dozens of genetic risk factors have been identified.

People suspected of having a DVT can be assessed using a prediction rule such as the Wells score. A D-dimer test can also be used to assist with excluding the diagnosis or to signal a need for further testing. Diagnosis is most commonly confirmed by ultrasound of the suspected veins. An estimated 4–10% of DVTs affect the arms. About 1 out of 9 people will develop VTE in their lifetime, with VTE becoming more common with age. When compared to those aged 40 and below, people aged 65 and above are at a 15 times higher risk. However, available data has been historically dominated by European and North American populations, and Asian and Hispanic individuals have a lower VTE risk than whites or blacks.

Using blood thinners (anticoagulation) is the standard treatment, and typical medications include either a direct oral anticoagulant or a 5-day minimum of low-molecular-weight heparin with warfarin followed by warfarin only therapy.

Prevention for the general population includes avoiding obesity and maintaining an active lifestyle. Preventive efforts following low-risk surgery include early and frequent walking. Riskier surgeries generally prevent VTE with a blood thinner or aspirin combined with intermittent pneumatic compression.

Signs and symptoms :

Signs and symptoms of DVT, while highly variable, include pain or tenderness, swelling, warmth, dilation of surface veins, redness or discoloration, and cyanosis with fever. Although, some with DVT have no symptoms.

Signs and symptoms alone are not sufficiently sensitive or specific to make a diagnosis, but when considered in conjunction with pre-test probability, can help determine the likelihood of DVT. In most suspected cases, DVT is ruled out after evaluation, and symptoms are more often due to other causes, such as ruptured Baker's cyst, cellulitis, hematoma, lymphedema, and chronic venous insufficiency.

Other differential diagnoses include tumors, venous or arterial aneurysms, and connective tissue disorders.

Pathophysiology

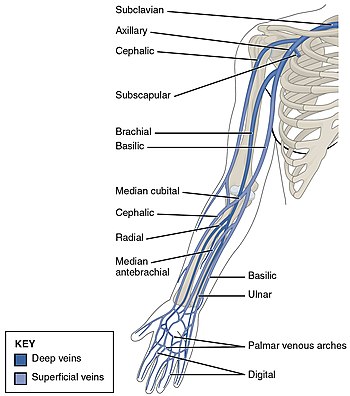

DVT often develops in the calf veins and "grows" in the direction of venous flow, towards the heart.[71] When DVT does not grow, it can be cleared naturally and dissolved into the blood (fibrinolysis). Veins in the leg or pelvis are most commonly affected, including the popliteal vein (behind the knee), femoral vein (of the thigh), and iliac veins of the pelvis. Extensive lower-extremity DVT can even reach into the inferior vena cava (in the abdomen). Upper extremity DVT most commonly affects the subclavian, axillary, and jugular veins.

The causes of arterial thrombosis, such as with heart attacks, are more clearly understood than those of venous thrombosis. With arterial thrombosis, blood vessel wall damage is required, as it initiates coagulation, but clotting in the veins mostly occurs without any such damage. The beginning of venous thrombosis is thought to be caused by tissue factor, which leads to conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, followed by fibrin deposition. Red blood cells and fibrin are the main components of venous thrombi, and the fibrin appears to attach to the blood vessel wall lining (endothelium), a surface that normally acts to prevent clotting. Platelets and white blood cells are also components. Platelets are not as prominent in venous clots as they are in arterial ones, but they can play a role. Inflammation is associated with VTE,[h] and white blood cells play a role in the formation and resolution of venous clots.

Often, DVT begins in the valves of veins. The blood flow pattern in the valves can cause low oxygen concentrations in the blood (hypoxemia) of a valve sinus. Hypoxemia, which is worsened by venous stasis, activates pathways—ones that include hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and early-growth-response protein 1. Hypoxemia also results in the production of reactive oxygen species, which can activate these pathways, as well as nuclear factor-κB, which regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 transcription. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and early-growth-response protein 1 contribute to monocyte association with endothelial proteins, such as P-selectin, prompting monocytes to release tissue factor-filled microvesicles, which presumably begin clotting after binding to the endothelial surface.

D-dimers are a fibrin degradation product, a natural byproduct of fibrinolysis that is typically found in the blood. An elevated level[i] can result from plasmin dissolving a clot—or other conditions. Hospitalized patients often have elevated levels for multiple reasons. Anticoagulation, the standard treatment for DVT, prevents further coagulation, but does not act directly on existing clots.

Compression ultrasonography for suspected deep vein thrombosis is the standard diagnostic method, and it is highly sensitive for detecting an initial DVT.[78] A compression ultrasound is considered positive when the vein walls of normally compressible veins do not collapse under gentle pressure.[18] Clot visualization is sometimes possible, but is not required.[79] Three compression ultrasound scanning techniques can be used.[78] Proximal compression ultrasound or whole-leg ultrasound are two of the options. Each technique has drawbacks: a single proximal scan might miss a distal DVT, while whole-leg scanning can lead to distal DVT overtreatment.[18] Doppler ultrasound, which is especially helpful in the non-compressible iliac veins,[79] CT scan venography, MRI venography, or MRI of the thrombus are also possibilities.[18][80] The gold standard for judging imaging methods is contrast venography, which involves injecting a peripheral vein of the affected limb with a contrast agent and taking X-rays, to reveal whether the venous supply has been obstructed. Because of its cost, invasiveness, availability, and other limitations, this test is rarely performed.[18]

This Article is free to use.

This article is on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_vein_thrombosis .

As claimed by Stanford Medical, It's in fact the ONLY reason this country's women get to live 10 years longer and weigh 19 KG lighter than we do.

ReplyDelete(And really, it has absolutely NOTHING to do with genetics or some hard exercise and really, EVERYTHING to do with "how" they are eating.)

BTW, What I said is "HOW", and not "WHAT"...

Tap this link to discover if this easy test can help you release your real weight loss potential